I recently finished writing The Ultimate Guide to Martial Arts Movies of the 1970s. In one section, I list my 20 favorite films of the ’70s before and after I wrote the book. Why? Because after watching 600-plus movies during an eight-month stretch, my list had 14 changes. That got me thinking about what would constitute the 10 movies every martial artist must see and why—hence, this article.

The 11 titles listed here—I couldn’t narrow it down to 10—aren’t the best martial arts films ever made or even my favorites. Rather, they were chosen for the impact they had on the genre, either by presenting new directions in fight choreography or by bolstering international appeal. Therefore, they’re listed in order of release date, not in order of preference.

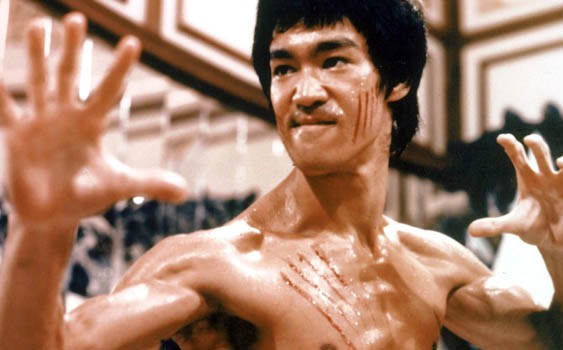

Martial Arts Movie #1: Fist of Fury (1972)

After the Sino-Japanese War (1894-1895), China was a fractured country, its pieces handed out to Japan and various European powers. Japan played a villainous role in Chinese history from that point on. Even after the nation’s defeat during World War II, the fear of economic backlash against the Chinese kept Hong Kong and the Republic of China mum about Japanese atrocities committed against the Chinese.

Bruce Lee’s Fist of Fury changed all that. His character defiantly defeated Japanese martial artists in 1909 Shanghai, when the city was under strict Japanese rule. Lee single-handedly crashed through that barrier of silence, giving the Chinese a sense of identity and pride. Although Story of Huang Feihong, Part 1 (1949) ushered in the second genre of Chinese movies known as gong fu pian (“kung fu film,” in which heroes fought with realistic skills), Fist legitimized it and brought international prominence to Hong Kong’s waning film industry.

Trivia: The scene in which Lee kicks eight attackers in the Japanese dojo is one unedited, wide-angle shot. It forever changed fight choreography.

Martial Arts Movie #2: The 36th Chamber of Shaolin (1978)

In response to the popularity of the kung fu movies Jackie Chan made at Golden Harvest, rival studio Shaw Brothers countered by having filmmakers Chang Cheh and Liu Chia-liang create a new genre called guo shu pian. Although translated as “national art film,” which implies that the national art is martial arts, guo shu films were designated as neo-hero movies because they focused on a new style of protagonist.

Directed by Liu and starring his adopted brother Gordon Liu Chia-hui as real-life hero Monk San De (one of the legendary “10 Tigers of Shaolin”), The 36th Chamber of Shaolin signaled the start of the guo shu film. It’s also important because it was the first movie to unveil the secret training methods of the ancient Buddhist monastery.

Martial Arts Movie #3: The Shaolin Temple (1982)

The importance of this movie parallels the importance of its star. Jet Li was born during a time when intellectuals and philosophers were persecuted, when the government outlawed martial arts and even destroyed temples and executed monks who refused to enter re-education camps. Li broke down those walls and became Communist China’s first actor to conquer Hollywood. He accomplished that feat by excelling in the cultural contraband of martial arts, philosophy and cinema.

The Shaolin Temple was China’s first live-action kung fu movie since the 1949 Communist takeover. It inspired the masses to visit the real temple’s remains and forced the paranoid government to warn the public that it was unnecessary to learn self-defense. It was also instrumental in introducing wushu to film fans worldwide.

Martial Arts Movie #4: Zu: Warriors From the Magic Mountain (1983)

With Zu: Warriors from the Magic Mountain, Western-trained, new-wave filmmaker Tsui Hark ushered in a fifth martial arts film genre that wasn’t officially named until it had run its course. Coined by yours truly, the Fant-Asia genre combined elements of sex, fantasy, sci-fi and horror with high-flying, gravity-defying wire work, far-out sight gags and over-the-top martial arts choreography. The film’s action director, Ching Siu-tung (the father of “wire fu”), dared to shoot the fight scenes at 18 frames per second as heroes zipped, flipped and flew at the speed of light amid explosions and magic weapons.

Martial Arts Movie #5: Duel to the Death (1983)

After the success of Zu, Ching Siu-tung directed Duel to the Death and proved that shooting old-fashioned sword fights at 18 frames per second didn’t make the action look hokey; it made it sing with gleeful, steel-slashing bewitchment. The movie intelligently weaves in the traditions of the classic chivalrous swordsman traveling down his path of martyrdom with a quasi-modern, German expressionistic visual approach that combines the elemental filmmaking sensitivities of Tsui Hark with Michael Curtiz’s swashbuckling style. What does all that mean? It’s a helluva fun film to watch!

Martial Arts Movie #6: Police Story (1985)

As the kung fu and guo shu films started to lose their luster—due in part to Hong Kong’s copycat mentality, in which the fights were becoming too repetitive—the 1980s witnessed the birth of the final two genres: Fant-Asia and the one defined by this movie. At the turn of the decade, Jackie Chan wanted to do something different, so he started to avoid period-piece films. His characters moved away from being practitioners of traditional kung fu and became more like extreme athletes, as seen in Dragon Lord (1982).

With his next film, Project A (1983), and more officially with Police Story, he created the wu da pian (“fight films using martial arts”) genre. It combined athleticism, martial-arts-influenced battles and outrageous stunts wrapped in modern themes and settings. Furthermore, instead of using traditional kung fu movements, the battles incorporated more Western-style boxing with karate-like kicks. Just about every contemporary-themed martial arts movie shot since is a result of Chan’s wu da style.

Martial Arts Movie #7: Drunken Master II (1994)

Based on fight choreography, Drunken Master 2 is arguably the best martial arts movie ever made. At the time of its release, Fant-Asia films were at their peak, and other directors were switching to Jackie Chan’s wu da style. Yet Chan returned to his kung fu roots to make a superior sequel. Filled with phenomenally fresh fights, it avoided the popular bobbing style of choreography used during Chan’s kung fu film heyday. His martial skills flowed like a waterfall over smooth rocks.

The final 16 minutes are as mesmerizing and creative as they are relentless and exhausting. Chan showed Hollywood, which had claimed any fight that lasted more than two or three minutes was boring, that a long battle could be exciting without having to repeat the same movements over and over.

Martial Arts Movie #8: The Matrix (1999)

Although not a martial arts film, The Matrix was the first mainstream Western movie to successfully blend Hollywood’s panache for visual effects with Hong Kong’s stylized fight choreography to create what’s still considered a phenomenon. Matrix is a visual spectacle. Its martial arts gags and imagery have been parodied ad infinitum, and the movie has become an integral part of 20th-century pop culture.

Trivia: Matrix inadvertently launched a ridiculous Hollywood trend. When the directors (the Wachowski brothers) approached Yuen Woo-ping to do the fights, he didn’t want to. He hoped that by asking for an exorbitant fee, he would turn them away. It didn’t work, however. Yuen then figured that by demanding that the main actors practice martial arts with him for four months, he’d be off the hook. Wrong again. Hollywood assumed that training actors for fighting roles was the standard.

Martial Arts Movie #9: Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon (2000)

To die-hard martial arts film fans, this movie was nothing new, but to the average American, Crouching Tiger was something never before encountered. Its twang of novelty resonated around the world as it became the first Chinese-language wu xia film to be widely accepted by Western audiences. Wu xia was the first genre of Chinese martial arts movie; its name translates as “martial chivalrous-hero film.” Originating in Shanghai in the 1920s, such movies were saturated with classical tales, heroic stories and legends of superhuman swordsmen and magical feats.

Directed by Ang Lee and fight-directed by Yuen Woo-ping, Crouching Tiger blended Eastern physical grace and action with American elements of performance intensity and the subtleties and nuances of European cinema. The movie was Lee’s homage to wu xia films, and it started a trend that brought international attention to similar motion pictures by other Chinese directors.

Martial Arts Movie #10: Ong-Bak: The Thai Warrior (2003)

Just when you thought good martial arts movies were the sole domain of China and the United States, the film industry of Thailand received worldwide acclaim. Tony Jaa’s Ong-Bak introduced a new and dangerous kind of fight choreography that combined wu da action with a stylized version of muay boran (the progenitor of muay Thai). The highlights of the movie are not only Jaa’s bouts with his meth-crazed adversary but also Jaa’s outrageous stunts: deadly knee-drop strikes, elbows of fury, far-out fire kicks and so on.

Jaa reminded us why we liked Jackie Chan’s movies from the mid-1980s. More important, Jaa’s efforts to showcase his nation’s fighting arts inspired other countries—including Vietnam, Indonesia and Malaysia—to follow suit.

Martial Arts Movie #11: Ip Man (2008)

Not since Drunken Master 2 has there been such a rip-roaring, old-school, kung fu movie. Ip Man arrived on the heels of those high-budget, high-production-value Chinese/American wu xia films shot in China using fancy wire work. It proved that traditional kung fu fight choreography reminiscent of the 1970s never goes out of vogue.

The kung fu is as real as the legitimate martial arts stars that perform the fights, which is no longer the case in most movies that feature actors who don’t practice or practitioners who are more into gymnastics than traditional kung fu. Not once does Donnie Yen, who plays Bruce Lee’s teacher Ip Man (also spelled Yip Man), break wing chun form to execute unnecessarily flashy movements to appease viewers who regard wushu-style fights as the real thing.

(For the past 18 years, Dr. Craig D. Reid has worked as a writer and martial arts film critic. He estimates that he’s watched more than 5,000 martial arts movies. He’s practiced martial arts for 38 years, and since 1979, he’s worked off and on as a fight choreographer in Hollywood and Asia. For more martial arts movie wisdom, check out his book, The Ultimate Guide to Martial Arts Movies of the 1970s: 500+ Films Loaded With Action, Weapons and Warriors).)

Related posts:

InfoMazza.com’s 25 TOP Posts of 2015

InfoMazza.com’s 25 TOP Posts of 2015

How Action Films are Made (Video)

How Action Films are Made (Video)

Legendary Fight Scene (Chuck Norris vs Bruce Lee) Way of the Dragon

Legendary Fight Scene (Chuck Norris vs Bruce Lee) Way of the Dragon

Fast and Furious 7 (2015), Cast, Posters and Trailer

Fast and Furious 7 (2015), Cast, Posters and Trailer

Minions, The Movie (2015)

Minions, The Movie (2015)

Mann Amade Am – by Faegheh Atashin (Googoosh)

Mann Amade Am – by Faegheh Atashin (Googoosh)

Built to be Bad – The 14 Most Jacked Movie Villains of All Time (with Photos)

Built to be Bad – The 14 Most Jacked Movie Villains of All Time (with Photos)

Oscars 2016: Leonardo DiCaprio Finally Wins His First Oscar for ‘The Revenant’

Oscars 2016: Leonardo DiCaprio Finally Wins His First Oscar for ‘The Revenant’

Posters of Upcoming Hollywood Movies (2017)

Posters of Upcoming Hollywood Movies (2017)

Baadshah Pehalwan Khan, The First Pakistani Pro Wrestler in WWE

Baadshah Pehalwan Khan, The First Pakistani Pro Wrestler in WWE

These 20 Superstars Had An Awful Childhood

These 20 Superstars Had An Awful Childhood

Diplo is Set for a Concert in Pakistan, February 2016

Diplo is Set for a Concert in Pakistan, February 2016